Remembrances

Paying the Price

CHRISTIANITY TODAY/May 12, 1989

The deaths of three college students on a missions project underscore the high cost of Christian service.

Two piles of stones mark the memory of three Westmont College students killed in March: One stands near Ensenada, Mexico, where they were serving on a week-long missions project when an auto accident ended their lives; the other stands on the Westmont campus in Santa Barbara, California, where they attended classes. The simple memorials—built by classmates, faculty, and friends—serve not only as a reminder of three lives lost, but also as a testimony to the hundreds of lives rededicated in faith and service in the wake of the tragedy.

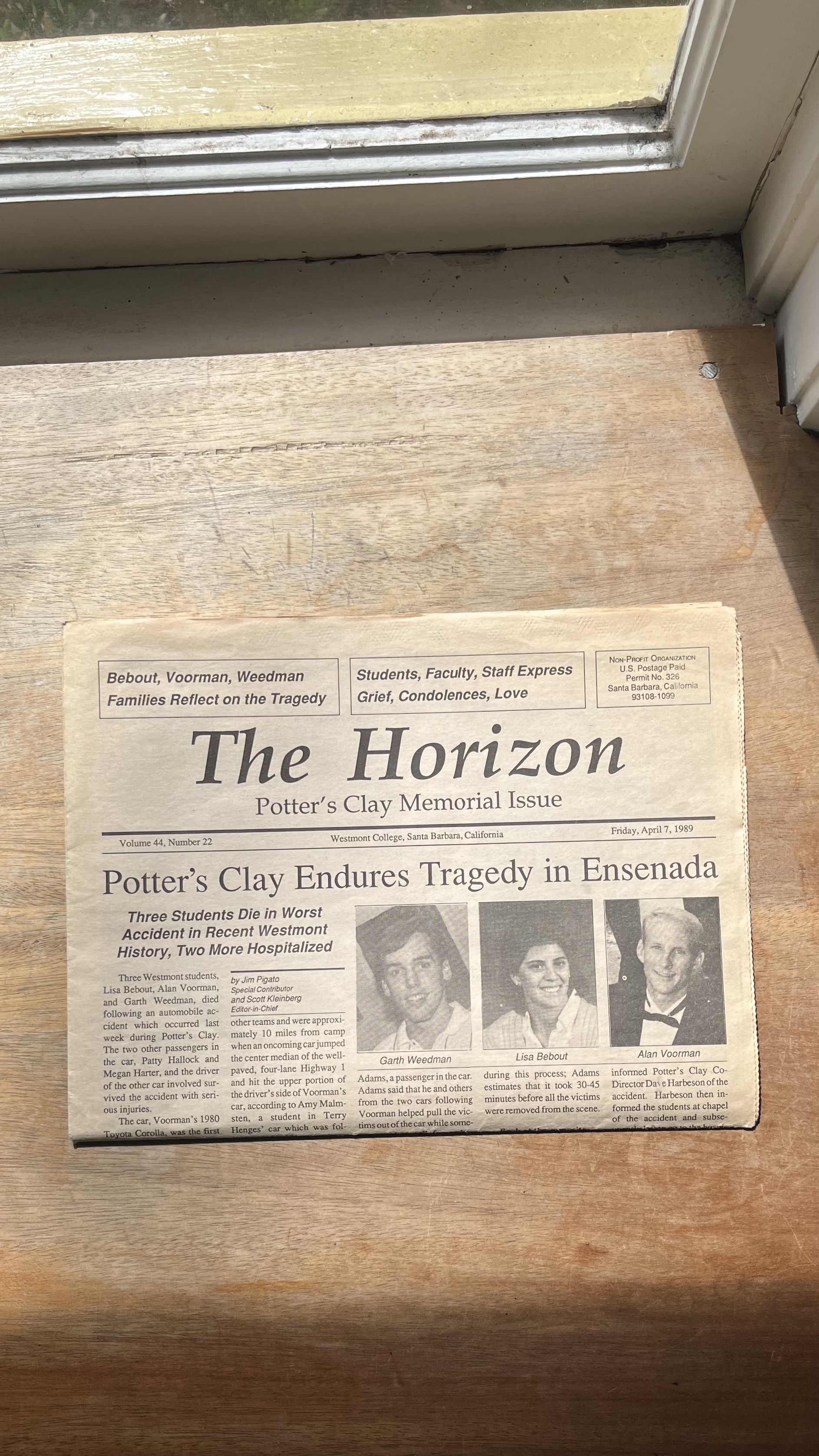

Lisa Bebout, Alan Voorman, and Garth Weedman were part of Potter’s Clay, a student-directed missions activity in which Westmont students build and repair homes, orphanages, and churches; provide medical and dental care; and conduct evangelistic out-reaches during their spring break. This year, 550 of Westmont’s 1,200 students paid their own way to live and work in one of Mexico’s poorest areas.

On the morning of March 27, the day after Easter, the three were driving to a work site in Ensenada when another car flew across the median of the four-lane road and struck their car head-on. The driver, Voorman, 22, a senior from Upland, California, died several hours after the accident. Bebout, 24, a senior from Mission Viejo, California, and Weedman, 19, a freshman from Mill Creek, Washington, were treated in Ensenada and transferred to a San Diego hospital, where they died the next day. Two other students in Voorman’s car, Megan Harten and Patty Hallock, were seriously injured.

When the accident occurred, other students following closely behind Voorman’s car stopped to help; others went for medical aid and carried news of the accident back to the Potter’s Clay headquarters, a tent city erected in a field outside Ensenada. Many students there, gathered for morning chapel, began a prayer vigil, while others contacted the college and rushed to the hospital.

The news had a devastating effect on the group, according to chaplain Bart Tarman, who was with them in Mexico. The rugged living and working conditions had already taxed the students, and the sketchy reports of the accident and the victims’ condition only raised anxiety. “They had to send their roots down deep into Christ, clear away some misconceptions, and realize it was okay to mourn and cry, if necessary,” Tarman said. In spite of the tragedy, students resolved to carry on their work. “I did not hear a single student even suggest they give up,” Tarman said.

Article continues below

Free Newsletters

Get the best from CT editors, delivered straight to your inbox!

Three Stones

Later in the week, as the project drew to a close and students prepared to leave Ensenada, guest speaker Gordon Aeschliman, editor and publisher of World Christian magazine, presented the idea for the memorials. Aeschliman had helped start Potter’s Clay 11 years ago while a Westmont student. He asked each student to find several stones from a riverbed near the field where they were camped: One large stone to build an “altar of remembrance” near their campsite, another large stone to take back to Westmont for a similar memorial there, and a small stone to keep as a reminder of their friends, their sorrow, and their resolve to live for Christ’s service.

The ministry of Potter’s Clay “grew up” during that week in Ensenada, according to Aeschliman. “The stakes went up, in terms of what it cost to carry out the work.”

More than 1,800 students, relatives, and community members gathered at a memorial service April 3, and after the service students gathered at a spot on campus to pile the stones they had brought from Mexico, pray, and sing quietly together. College faculty counseled with students throughout that day and week, helping them deal with their grief.

“In a secular environment, people rush to put an experience like this behind them, to get away from the emotion and trauma,” said Westmont president David Winter. “On our campus, we wanted to continue in that grief process as long as God had something to say to us. We encouraged students to use those days and weeks to learn as much from God as they could.

“These students are serious about using their lives in Christian service,” Winter said. “They are grieving, but are not at a loss.”

The tragedy also forged stronger bonds between Westmont and Ensenada. A group of Ensenada pastors, their families, and a doctor who had worked with the Westmont group drove through the night to attend the memorial service. “We have grown to love you as partners,” pastor Roberto Ninos told the audience. “You have paid the high price, you have given your lives to us. The Christian community in Ensenada will never be the same.”

Sign-ups for next year’s Potter’s Clay will not begin until January. Student leaders expect the turnout to continue at around 500, which is as many as the program can handle. The mood, however, will be different. “I think we’ll see a more sober judgment of the cost,” said Dave Harbeson, codirector of Potter’s Clay. “As one friend said to me, ‘We’re in a war, and there are casualties to be expected.’ ”

Article continues below

Many students have indicated they are rethinking their career plans in light of what has happened, Tarman said. “Tragedies like this can be a window on the upside-down thinking of the Gospels that says invisible things are the most important and the visible things are the least important.

“In a real sense, Lisa, Alan, and Garth gave their lives while doing the kingdom’s work,” Tarman said. “I think that builds an ethos on the campus, a witness of service, that will continue to be a part of the tradition here for years to come.”

A Potter’s Clay Memorial Fund has been established to assist families of the five students involved in the accident. Contributions will help cover medical expenses; any excess funds will support the work of Potter’s Clay.

By Ken Sidey.

Link to original article: https://www.christianitytoday.com/ct/1989/may-12/missions-paying-price.html

Do you have a Potters Clay 1989 story that you would like to share? Please record your memories below.

After reviewing your submission,

we hope to share your memory.

WHAT PEOPLE ARE SAYING

Hope in the Darkest Hour is a compelling narrative that offers a powerful message of resilience, faith, and hope in the face of adversity. The book follows Megan's journey through the trials and tribulations of life after a near-death experience, weaving together themes of spirituality, personal growth, and the transformative power of hope.

Through Megan's poignant recounting of her experiences, I was drawn into her world, experiencing the highs and lows of her emotional and spiritual journey. Despite facing numerous challenges, Megan's unwavering faith and inner strength shine through, which inspires me to find hope and courage in my own life.

One of the most striking aspects of the book is Megan's ability to find meaning and purpose in the midst of adversity. Her journey is not just one of survival, but of profound spiritual awakening and personal growth. From graduating with her bachelor's degree to revisiting the site of her life-altering accident, Megan's story is a testament to the resilience of the human spirit and the power of hope to overcome even the darkest of times.

While Hope in the Darkest Hour offers a compelling glimpse into Megan's life and journey, I found myself wanting more. The book leaves lingering questions about Megan's life beyond the years covered in the narrative. What challenges did she face after graduating? How did her near-death experience continue to shape her outlook on life? While the book provides a satisfying conclusion, I was left longing for further insight into Megan's ongoing journey of healing and self-discovery.

Overall, Hope in the Darkest Hour is a captivating read that offers a profound message of hope and inspiration. Megan's story serves as a reminder that even in our darkest moments, there is light to be found, and that through faith, resilience, and perseverance, we can emerge stronger and more whole than we ever thought possible.

~ SARAH

© Copyright 2024. Hope in the Darkest Hour. All rights reserved.